If you have a corporate network, you will often have heard your network administrators mentioning a dangerous sounding word called ‘firewall’. When you ask if a specific thing can be allowed, they say, “The firewall blocks it. We need to reconfigure it to allow.”

What exactly does this mystic sounding name represent? Why are network administators obsessed with it and how does it protect your company’s network? Read on to find out one of the most important building blocks of network security.

One sentence: what does a firewall do?

It protects your organisation’s network by blocking or redirecting traffic that’s not supposed to be in your network. Only the computers inside the organisation can access the file sharing server. Computers from the world wide web can only access the content on your organisation’s web server. At an airport, all the users who have not signed up should be redirected to the sign up page regardless of whatever website they requested on the browser.

Why is it called a firewall?

The nomenclature is based on the imagination that no one can pass through a wall of fire unless someone on the other side of the fire controls by choosing to blow a hole through the flame to let someone pass through.

How a firewall works

Each machine connected to the Internet has a unique numerical called an IP address. An IP address is an address comprising of 4 numbers, each one from 1 to 254. The numbers 0 and 255 are used for special purposes, but we will not cover them in this post. There is a special IP address called 127.0.0.1. This address is called the home address and used by each machine to talk to itself.

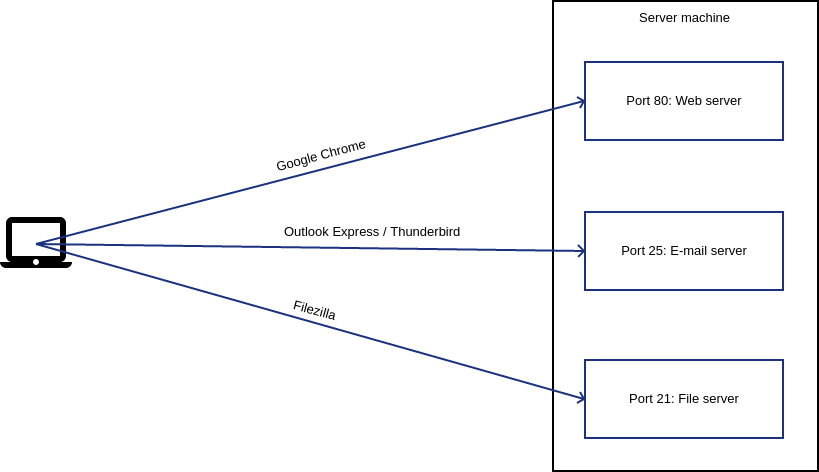

Within each machine, we can say that there are 65536 doors. These doors have numbers from 1 to 65536. The doors are called ports. Each port is used by a specific software application to talk to other machines over the Internet. Plenty of ports between 1 to 1024 are used by certain software applications as a convention. To break this convention would be to confuse a lot of established software applications. E.g. By default, web browsers expect websites to be available at server’s port #80. While requesting for a website, the web browser in your machine will always knock on the server’s 80th door by default, unless the typed URL specifies a different port explicitly. Your Outlook Express or Thunderbird will always knock on port number 25 of an email server to send emails. The banking app on your phone will most likely knock on port number 443 of your bank’s server.

That’s it in a nutshell. Whenever two computers talk over the Internet, one machine starts by knocking on a certain door of the other machine and waits for the response. Following this, the conversation goes on.

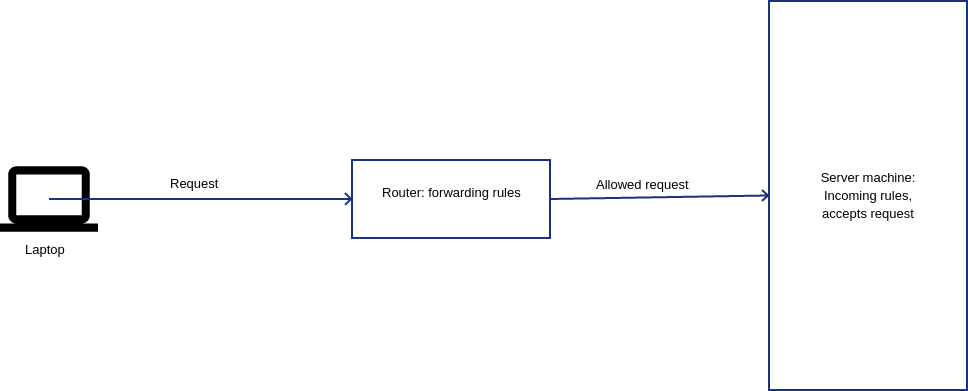

A firewall intervenes by either allowing or blocking the conversation between the two machines to continue after the initial knock. Think of it as a watchman opening the door of your host’s home and verifying your intentions before calling the host to have a conversation with you. If the watchman is convinced that you are an imposter, then you are snubbed. Similarly, the host may not want to be disturbed at certain hours of the day, nor will they want to entertain more than a certain number of guests at the same time. Under these circumstances, the watchman will not allow you to meet the host.

The watchman can either snub you rudely (BLOCK) or politely tell you that the host is not available along with a good reason (REJECT).

Controls that a firewall can impose

Based on where the firewall is written, two types of traffic can be controlled.

Incoming traffic

This is used to control what type of traffic specifically intended for this machine can the machine accept. E.g. if this machine is a web server, then packets addressed to this machine’s port 80 will be accepted, whereas those to its port 25 will not. If this machine is an FTP server for transferring files, then traffic to its port 21 will be accepted. As a real world example, let’s say that you run a club that has a swimming pool and not a gym. If someone asks to visit the gym, you would turn them away saying that there is no gym in your club. You would only allow those seeking a swimming pool. Allowing gym seekers into your club and have them do nothing is just a waste of space in your club and causes unnecessary crowd. So you would politely bump them off the place.

If the machine should only accept traffic from other computers in the organisation and not from others in the Internet, this too can be controlled. Let’s assume that your club is exclusively for the residents of a particular locality and not open to public. You would check some form of ID which verifies if someone is indeed a resident, before letting them in. Firewalls can do the same by checking for IP addresses of the local network (also called LAN).

Let’s say for some reason that you need to run your web server software at port 80 instead of 8080, you can arrange for the firewall to make all requests made to port 80 to automatically go to port 8080 instead. Let’s picture this from the real world. Conventionally, you would automatically drive to a facility’s parking lot to park your vehicle. But what if the parking lot is under maintenance. A sign will typically be put up at the entrance of the parking lot, regretting the inconvenience and directing you to another parking lot kept ready for the day.

Rules for incoming traffic are written on servers which run software, such as web servers, email servers, file servers, etc.

Forwarding traffic

Forwarding traffic is written in machines that act as gatekeepers between two networks, such as network routers and proxy servers. A classic example is that of the WiFi routers in airports. To allow you to access Internet from within the router’s WiFi network, the router makes the request from your phone or laptop go through a set of rules that redirect you to a landing page where you sign up by giving your phone number or email. There are higher speed or longer time plans for which you can pay to continue.

Forwarding rules can accept traffic between two networks, reject them or redirect them somewhere. Let’s say that your organisation does not allow Facebook. Then the WiFi router will have rules stating that any packet bound for Facebook server’s port 80 should be blocked. However if Gmail is allowed, then there will be rules saying that traffic bound for Gmail’s port 80 (for HTTP) and port 443 (for HTTPS) should be allowed. For situations like airport WiFi, the router will save a list of all the IP addresses (of phones and laptops) who have already signed up and authenticated. For others, another rule will be triggered. This rule will tell the router to redirect the unauthenticated devices to the web server that contains the login page and the software for the users to sign up.

Conclusion

As you can see, firewalls are the building blocks of security and access control while setting up your organisation’s network. It is worth spending plenty of time setting up, learning and maintaining firewalls to keep your organisation’s network secure.