In the last post, we saw how version control system such as Git helps three poets, i.e. Nancy, Tommy and yourself write a poem and maintain several versions of it in a secure database, so that you can go back to an older version and start over again if you wanted to. We saw how only the changes across each version is saved. We also saw how the poets commit their own changes to a local repository, push them to a central repository and pull others’s changes into their own repositories.

In this post, we will see more advanced concepts such as branching, merging and conflicts. Fear not, these hard to understand concepts will be explained in a lucid manner.

Climbing on your own branch

We saw that the three poets make changes and push to the central repository. We saw how the central repository stores changes in rows of records, each row containing the list of changes application from the previous version to the version indicated by the row. The rows show the history of the poem in a linear line. You’d be forgiven to think that version control is a tabular database with changes in an every increasing straight line.

But this is not how things work in real life. The poets split the linear history in the form of a tree. Instead of one single line showing the entire history of the poem, the repository is shaped like a tree, with several branches growing off the main trunk. This main trunk is called the trunk or the master branch, with several branches emerging from it. But unlike a tree’s branches, the version control branches rejoin the master branch at a point different from where they diverged. These two concepts are called branching and merging.

Branching and merging are used so that the poets can safely experiment with their poem in a branch of their own and keep committing their changes without polluting the master branch, which is meant only for the version of the poem that will be seen by the public. Usually the author-specific branches are named in the format <author>/<reason>, i.e. the name of the poet and the reason why the changes are being made.

Here is an example. On the master branch, our poem has progress this far.

Mary had a little lamb, little lamb, little lamb.

Mary had a little lamb, its fleece was white as snow.

Now each of our poets decide to brainstorm new ways to describe the relation between Mary and her lamb. But they will now stop editing the poem on the master branch and instead each poet will make his / her own branch from the current point on the master branch.

Nancy wants to write that the lamb goes everywhere Mary goes. So she starts a new branch named nancy/lamb-goes-everywhere. She adds the following lines.

And everywhere that Mary went, Mary went, Mary went,

and everywhere that Mary went, the lamb was sure to go.

Tommy wants to describe the day when the lamb decided to go to school with Mary. He starts a new branch named tommy/lamb-goes-to-school and adds the following lines.

He followed her to school one day, school one day, school one day,

He followed her to school one day, which Mary didn’t like.

You decide to take a little break from poem writing and do not add your own branch. Instead you decide to wait for the others to write some lines, from which you will write further.

Merging

After the above additions to the poem, it is time to merge the two branches into the master branch. Let’s assume that the poets agree to merge Nancy’s branch first, followed by Tommy’s. Both Nancy and Tommy started a branch from the commit 3 of the poem (see last post to learn what commits are and why we are on commit 3). While merging, all the changes done since a branch diverged from the master branch are taken into account. In Nancy’s case, those are the lines about the lamb following Mary everywhere. For Tommy, the changes since he created his branch are the lines describing the lamb going to school.

When Nancy’s branch is merged into the master branch, her lines are automatically incorporated into the latest commit. Same thing happens for Tommy’s branch. The poem when taken from the master branch now looks like so.

Mary had a little lamb, little lamb, little lamb

Mary had a little lamb, its fleece was white as snow.

And everywhere that Mary went, Mary went, Mary went,

and everywhere that Mary went, the lamb was sure to go.

He followed her to school one day, school one day, school one day,

He followed her to school one day, which Mary didn’t like.

You have been sitting idle all this time. But you can now pull (read about a ‘pull’ operation from the last post on version control basics) everyone else’s changes and get the latest version of the poem.

Conflicts

Version control usually chugs along just fine. It automatically finds out the right places to apply everyone’s changes and keep the content intact.

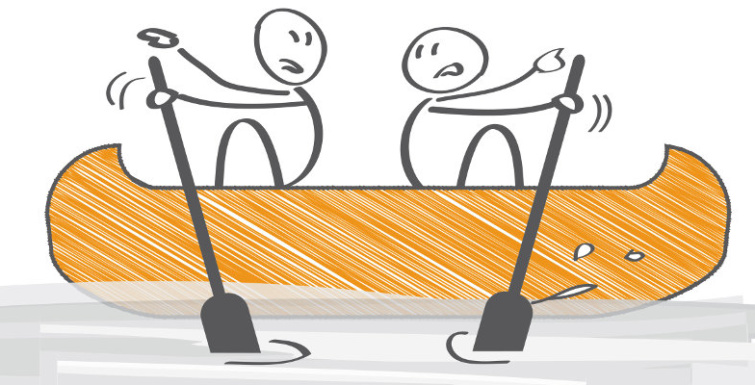

However, there are times when version control is confused and it has to seek guidance from the users to find out how to apply changes. This usually happens when two users edit the same lines in a file. Or in other crazy situations such as when one user edits a file, while another user deletes it. In such a case, the system raises a conflict and doesn’t allow further changes until conflicts are solved. Let’s see an example.

Nancy doesn’t find the phrase “which Mary didn’t like” appealing and wants to change it to something cuter. So she makes a commit which looks like this:

He followed her to school one day, which the students found amusing.

Meanwhile, you are itching to contribute. You too didn’t like the same phrase and commit your own change.

He followed her to school one day, which was against the rules.

Depending on who is going to push his / her own changes second, that person will receive a conflict message. Both persons have been trying to change the content of the same line and the version control cannot decide which one to use.

On receiving a conflict, the two persons sit down and work out a solution. So it is up to Nancy and you to talk and agree upon which changes should be part of the poem. To resolve a conflict, it is possible to chuck both of your ideas and go back to the original line. Eventually, it is up to the compatibility of the teams, a good team leader and a solution-oriented approach to make the rightful changes and proceed.

Conclusion

Over the last two posts, you learnt how a typical version control system like Git works and how you can maintain a system safely such that you can go back and forth among version, be it a children’s poem or the program to launch a rocket. The next time you see the squiggly coloured lines on your version control tool showing the branches of a Git repository, you can come back to this post and understand what’s going on. You will understand those coloured lines a little bit better.